Parental care begins with the birth of the first child. Although they are faced with all the complexity of this task for the very first time, overwhelmed with new experiences, parents do not begin their relationship with their infant by learning day by day, gathering experiences one at a time. Part of the preparations take place during pregnancy, when parents are getting ready for their new role in both the emotional and practical sense. Marital relationships are especially important in the antenatal period. Dissatisfaction with one’s marriage, oneself or one’s job often translates into dissatisfaction with one’s role as a parent, which turns child care into a source of discomfort, strain or stress. Research into early infant–parent relationships conducted in the 1970s and 1980s point to the central role of parental responsiveness to infant signals. Parental responsiveness is the basis for parental influence on the infant’s cognitive, linguistic and social development. Maternal capacity to receive and appropriately respond to these signals is constant, although the complexity and demands of these signals increase dramatically during the first 3 years of infant development. Basic knowledge of the role of maternal responsiveness is important for the further development of organised structures of social interactions, such as attachment relationships. The organisation model of the attachment theory provides the most extensive portrayal of the function and development of the parent–infant relationship during the first 3 years of life. After the first 2 months, infants enter a stage in their development marked by significantly more intense social communication. During this period, the mother and infant primarily communicate “face to face” (feeding, changing, playing), which provides space for new ways of communication. These relationships demonstrate the tendency of the mother and infant to modify their behaviour in response to each other. The more skilful (or capable) the mother is in adapting and responding to the infant’s behaviour, the more successful the infant will be in responding to her signals. In essence, this is a process of mutual affective attunement. In the period between 3 and 9 months of age, the percentage of coordination between maternal and infant behaviour (appropriateness of response to received signals) gradually increases. Successful experiences that are frequently repeated become internalised, memorised and allow reactions in future communications of the same type to be predicted. Identified and memorised experiences contribute to the processes of self-building and distinguishing one’s own being from the environment. As the child’s psychomotor skills develop and communication experiences (for both participants) are gathered, there is an increase in the percentage of successful responses and a decrease in the time necessary for their identification. Initially, inadequate responses are more frequent; they are then corrected and followed by different responses. This is a process in which infants learn to modify their activities so as to elicit the desired response. This makes the interactive communication more dynamic as infants learn how to correct their mistakes and make their signals more effective. According to Trevarthen, infants are born with the ability to express emotions as well as intrinsic motivation to establish affective communication. Based on these observations, Trevarthen calls the first months a period of “primary intersubjectivity”. The term is meant to highlight the processes of organising communication potentials (opening communication channels, the ability to recognise, process and reject received emotions). The infant gradually develops the ability to connect and express individual emotions through appropriate and differentiated movements, voice, glances, etc. Once established, this mechanism is used in interactive communication with the mother to ensure adequate responses (satisfying one’s needs) in the next stage of development (2–6 months of age). A 6-month-old infant already has plenty of experience, has developed a series of communication (behaviour) patterns with the mother, as well as the ability to anticipate, when faced with previously experienced situations. At the same time, motoric and cognitive capacities which place the infant in interaction with other persons and experiences increase. The infant is put in a situation that implies unfamiliarity and uncertainty. At this stage of maturation, the infant turns to close individuals (mother, father) for interpretations of new situations and instructions on how to behave. This process is known as social referencing. Around the age of 1, infants are gradually separated from their mothers. Less dependent and more mobile, they begin to explore their environment and their own abilities. Movements away from the mother expand and become more frequent. However, children know that their mothers are always close by and take care of them even when they are not near (e.g. after they have gone back to work). At this age, children often have an object (toy, blanket, pacifier) which they always keep close and which comforts them and helps them fall asleep. This is the so-called transitory object, a maternal substitute of sorts. It is always there when the child needs it and helps in difficult situations if the mother is not around. The mother’s failure to efficiently adapt results in inadequate, uncoordinated responses to the child’s signals (needs). This deeply interferes with the internal organisation and exacerbates the processes of self-building and interpreting signals from the environment. Such children display disorganised behaviour towards their mother as well as their peers. Children who cannot elicit adequate maternal responses and satisfy their affective needs use internal protective mechanisms to eliminate the feeling of discomfort. The infant may activate one of several behaviour patterns, such as self-comfort (turning away from an unpleasant sight, sucking the thumb), auto-stimulation (rhythmic movements, making monotonous and calming sounds, surface stimulation of individual body parts), etc.

Negative influences on early affective relationship development

The infant–parent relationship exerts a strong influence on the infant’s physical, psychological and social development. Disturbances in these relationships, caused by separation or traumatic and painful experiences with parents, deeply interfere with the child’s development. The detrimental effects of the lack of parental care were identified among children who, due to the loss of both parents or the parents’ inability to care for their children, were placed in institutional care (orphanages). Spitz’s 1945 paper describes high mortality rates among institutionalised infants and psychological problems among children who had spent a long time in children’s homes, where one person was responsible for the care of 8 children (these people would often change). Each child could spend only a brief time with the caregiver, which did not allow for the establishment of deeper emotional bonds. Beds were separated by curtains, thus preventing communication between peers. Children grew up in isolation, almost without any external stimuli. These children were susceptible to infections which often proved fatal. The average weight and height was below the lower limit of normalcy, while developmental quotients gradually deteriorated (from 124 at the beginning of institutionalised life, through 75 at the age of 12 months, to 45 in the second year). Studies suggest that life in homes which provide the child with ample support (nutrition, creative work) reduces the negative effects of institutionalisation on the development of intelligence; however, the problem of social deprivation – caused by the inability to form deeper emotional bonds (caregivers frequently change) – still remains. Impairments caused by the child’s institutionalisation can quickly be corrected by placing the child in a family. These findings have prompted experts to increasingly promote child adoption.

Maternal emotional problems

Parenthood (parental care and love) is necessary for the child’s overall normal development. Psychological and psychiatric disorders of one or both parents have a profound impact on the infant’s health. Since the person most in contact with the infant during the first year is the mother, the majority of research into this problem is focused on maternal illnesses. Considering the complexity of this problem, relevant sources provide different approaches to studying maternal psychiatric illnesses: from examining genetic factors that caused illnesses in the child, through social factors which often accompany maternal mental illness (poverty, marital problems), to studying disorders in intersubjective relationships between the mother and child. The first condition for the establishment of early relationships is the mother’s availability: the fact that she is there for the child. It is difficult to imagine a situation which does not allow for an intersubjective exchange of emotions (communication). In situations like this, the individual (in this case, the infant) is in complete isolation, devoid of the possibility of emotional and cognitive development. In real life, this happens with psychotic mothers or children who were institutionalised at the beginning of the 20th century, due to abandonment or maternal illness. It is important to realise that in situations like this the clinical image of the child may be inconspicuous. The child may seem well cared for, and the mother appear caring. However, closer analysis reveals an absence of appropriate content in early mother–infant relationships. Everything remains on the surface, while the content level is marked by emptiness or non-attunement between infant needs and maternal responses. After numerous unsuccessful attempts to establish communication with the mother, the child withdraws, stops sending signals and begins to comfort himself by sucking or rhythmically rocking his head or body. After a while, the infant will once again try to establish communication; however, repeated failures once again prompt him to turn to his own self-defence (comfort) mechanisms. With time, this pattern of behaviour becomes habitual and creates a deep sense of failure to elicit response in others, as well as a feeling that the mother is unreliable, and the world around the child worthless. This leads to infant depression which is not the result of maternal depression, but the infant’s inability to interact with his environment. When the mother is emotionally unavailable (depressed, disinterested, overly frightened, preoccupied with other problems, etc.), the infant cannot elicit a response, which makes him depressed and triggers a deep feeling that he is unable to establish communication with the outside world. Mothers with emotional problems are unable to recognise infant signals and respond to them appropriately. Typically, the mother responds in an inappropriate way or fails to respond altogether, thus neglecting the infant. Sometimes, the mother feels the infant needs something and responds by providing the infant with many unnecessary things. Such infants appear overprotected: on the surface, one might say they are surrounded by love and attention, but their basic needs are not met. Their basic signal (request) leads to various unnecessary things. These infants are also essentially neglected. For a long time, postpartum depression was considered one of the most important pathogens (stressors) for infant development. Epidemiological studies have shown that around 10% of women experience non-psychotic postpartum depression in the first 3 months. Irritability, anxiety, poor concentration, and depressive moods and thoughts clinically accompany this depression. These symptoms can have a profound effect on interpersonal relationships, including the relationship with one’s infant. The biggest incidence occurs during the first 3 months after delivery, which coincides with the period Winnicott identifies as the primary phase of maternal preoccupation, when maternal physiology adapts to the infant’s functioning. At the same time, the infant adapts to external conditions of life and parental care, and is extremely sensitive to the quality of their interpersonal contacts. Observations that identify the occurrence of distress and avoidance in cases of experimental discontinuation of the infant’s communication with the mother confirm this. Such a high frequency of postpartum depression and problems in early relationships with the infant appear even more important, considering that in most cultures the mother assumes the role of primary caregiver and provides the primary environment for the infant. In contrast, and significantly rarer, amounting to only 2-3‰, the mother suffers from a severe form of postpartum psychosis. However, considering the high incidence of postpartum depression, the fact that the mother is the dominant factor in the relationship with the infant, and given the infant’s sensitivity to the quality of interpersonal relationships, it is important to consider possible negative influences on infant growth and development. The past two decades have seen numerous studies which show that children born to depressed mothers display behaviour disorders. Some suffer from depression disorders, others from conduct disorders, and some are hyperactive. The lack of reciprocal cognitive stimulation leads to cognitive development impairment in children born to depressed mothers. Infants born to depressed mothers are more often born with low birth weight (this contributes to maternal depression), sleep more during infancy, cry more often, are more restless and are prone to opisthosomas. The length of the observation and the difficulties in obtaining longitudinal insight into the mother’s health make it difficult to determine the differences in the permanent consequences among children whose mothers are permanently depressed and those whose mothers were experiencing a depressive episode at the time of the experiment (the first postpartum months). However, it seems that negative consequences are visible for a long time even after the remission of depression. As many as 58% of children aged 8 still display behaviour disorders present in the third year, even though the mother no longer displays symptoms of depression. Observations of mothers and infants suggest that depressed mothers communicate less with their children and participate less frequently in positive stimulations of the child during play. At the same time, their infants engage in affective communication (smiling, showing the mother toys, vocalising while playing together) less frequently and express more intense signs of distress at the mother’s departure. For the most part, these mothers are preoccupied with their own problems and are consequently less sensitive to the needs of their children. An estimated 20% of children experience some difficulties when only the mother has emotional problems, while 43% experience difficulties when both parents have emotional problems. The effectiveness of curing postpartum depression via early intervention in the form of support and counselling points to the need for early diagnostics of mothers with increased risk of depression. Prenatal marital problems, low socio-economic status, absence of a close and reliable person and previous psychiatric illnesses are considered to be reliable indicators of a heightened risk of postpartum depression. Furthermore, negative responses to the infant, difficulties feeding, bad moods or proneness to crying, lack of family support (absence of visits or superficial communication during the visits) in the postnatal period all point to a heightened possibility of postpartum depression.

Poverty and single parenthood

Poverty and its side effects affect the infant’s health from the moment of conception. Medical histories of impoverished mothers more frequently reveal risk factors (illnesses, habits), bad antenatal care (in the general sense of the word), and display more signs of stress and unhealthy habits during pregnancy. Statistics suggest that every fourth impoverished mother in the US took narcotics during pregnancy. This exposes the infant to acute or chronic intrauterine stress. Premature delivery and insufficient growth for the gestation age (infants born at low birth weight) are more common. These infants are more vulnerable from the point of view of constitution, and more difficult to raise and care for. The same factors are at work after the delivery, which creates a discrepancy between the infant’s increasing demands and the mother’s limited physical and emotional capacities. Overcome with stress, mothers with restless infants who cry a lot often turn away from their infants if they are unresponsive to their attempts to comfort them. Once established, this type of negative communication pattern is difficult to alter and permanently disrupts the infant’s growth and development. Not only are impoverished children born as more vulnerable, the influence of prenatal factors makes healthy children in impoverished families vulnerable due to inadequate care and nutrition. They often develop deficiency diseases (anaemia, rickets, malnutrition), and lead poisoning (old buildings painted with paints which contain up to 50% lead, lead water pipes), more frequently die of diseases of the respiratory tract, diarrhoea, malaria and AIDS (WHO Global Database), and fall victim to injuries and poisoning. Due to their vulnerability, impoverished infants require better healthcare. However, due to their status, healthcare is less available to them. Another result of poverty is higher post neonatal mortality caused by poor living conditions and specific parental problems (National Commission to Prevent Infant Mortality, 1988). According to one Washington study, post neonatal mortality in a population living on welfare was around 10.1‰ (compared to 1.4‰ in the rest of the population). An estimated 10% of the poorest children in the US are living on the street; around 35% of homeless women were pregnant; 26% of homeless women gave birth in the previous year. Children without shelter are at increased risk of health and development problems. Living in such conditions influences parental care, interpersonal relations within the family, and daily infant care and upbringing. Irregular (sometimes even chaotic) sleeping, waking, feeding and changing schedules, frequent changes of caregivers and places where the infant sleeps mark the lives of families living in abject poverty. Prematurely born infants of impoverished parents spend more time with family and friends than infants born to wealthier parents. In situations like this, the infant often forms attachments with persons who are not members of the household. In many poor families, the marital status is not regulated. On the other hand, an estimated 80% of unmarried fathers do not live in the same household as their children. The role of the father in situations like this has not been sufficiently researched. It seems that only a small percentage of fathers are able to assume full responsibility, while the majority accept their paternal role only partially and participate in the life of the family under certain conditions (focusing on the mother and little ones who call him “daddy”) which do not limit his freedom. In this type of family, the maternal role is often assumed by the grandmother who may (whether consciously or subconsciously) be trying to rectify the mistakes she made when raising her own children. The lack of daily structure and continuity undoubtedly interferes with the child’s normal emotional development. In a way, each child shapes their parent. Each child tests the emphatic capacity of their parents: less demanding children can therefore progress even with parents with reduced emphatic and physical capacity, while “difficult” children may completely drain even parents with ample capacities. Poverty increases the possibility that the child will be difficult to raise. At the same time, poverty reveals and increases the effects of parental vulnerability (childhood abuse, psychiatric illnesses in the family). Poverty further produces new stressors, such as unpleasant neighbourhoods, neglected or overcrowded households, dehumanisation, loss of control over one’s destiny and dependence on welfare. Put together, all these factors become the focus of the parents’ attention (drawing it away from the infant), exhaust their physical and emotional energy, and put their patience, feelings of competence and control over their destiny to the test. All this generates paralysing feelings of rage, irritability, tiredness, incapacity and hopelessness which, when combined with exhaustion, disrupt the parents’ ability to communicate with their children. The ability to recognise the infant’s affective needs and signals and provide appropriate responses (coordinated communication) has largely been inhibited. The mother suffers from frequent mood swings, sometimes triggered by crisis situations, but occurring with no apparent cause. Their children are also prone to mood swings and may be angry one day, happy the next, and then fail to convey any emotion at all. In crisis situations, mothers who show awareness of infant needs tend to place them in second place and focus on dealing with more pressing problems. It seems that parents are less likely to adapt to the needs of their infants and instead mostly expect infants to adapt to their possibilities and conditions. Children in impoverished families do receive a lot of love from their parents, grandparents and other family members; however, this mostly happens when adults have time and feel a personal need to communicate with the child. The child is unable to establish communication when he wants or needs to. Focus on tasks related to infant care, feeding and welfare often result in neglecting play time and emphatic responsiveness. Often troubled by memories of their own impoverished childhoods, the mothers primarily focus on ensuring food, diapers, clothes and other things typically lacking in poverty. Fun and playing with the infant are often perceived as luxuries they cannot afford. These mothers less frequently enjoy playing with the child and typically try to control (dictate) the mode of their interaction.

Adolescent motherhood in normal living conditions

Reports published in 1991 from the US National Center for Health Statistics warn that ¼ of young girls below the age of 19 get pregnant. Adolescent pregnancy leads to adolescent parenthood which forces young women – still children themselves – to assume the great responsibility of motherhood. A study conducted by Džepina et al. among Croatian adolescents in 1990 shows that more than half of the participants practise unprotected sex; 4.5% of sexually active adolescents became pregnant, and 1/5 of them gave birth. In normal living conditions, adolescent parents face numerous problems. Young people, capable of sexual reproduction but not grown-up, cognitively and psychologically immature, with only a few legal rights, for the most part have difficulties facing the responsibility of parenthood. The cognitive immaturity of adolescents and other development factors turn the attention of young adults towards themselves. This can mean that they will pay less attention to their children, be less able to identify the needs of their children or simply place their own needs before those of their children, all of which decreases the overall quality of parenthood. Fundamental problems of adolescent parenthood are linked to growing up in a biological, cognitive, psychological and social sense in an environment marked by chronic stress, further exacerbated by poverty, limited education opportunities and familial instability. In most cases, adolescent mothers suffer permanent and/or temporary psychological, social and economic difficulties. Osoffski and Hann argue that, compared to adult mothers, adolescent mothers increasingly face identity dispersiveness, a lack of confidence and are more prone to depression, lack of self-confidence and trust issues. Reliable and important indicators suggest that depressed mothers are more emotionally distant and less dedicated to their children; moreover, many of them are at increased risk of physical aggression towards their children, which certainly implies that the children themselves are at greater risk of affective problems. Poverty and privation strongly contribute to the problems faced by adolescent mothers. They increase the risk of numerous exacerbating circumstances, including life on the edge of the law, frequent moving, difficulties in dealing with daily tasks, difficulties in raising children and a lack of emotional and social support. In addition to this high-risk socio-emotional environment in which adolescent parents live with their children, indicators of cognitive problems have also been observed. Many adolescent mothers spend little time talking to their children. This is likely to lead to limited verbalisation on the part of the child. Living in a cognitively poor environment, such children are undoubtedly exposed to increased risk of behaviour and/or learning disorders, especially when entering organised school systems. Numerous studies describe adolescent mothers as having insufficient knowledge of the developmental needs and the developmental perspective of their children, compared to adult mothers. The latest research by Fusrtenberg, Baranowsky, Schilmoeller and Higgins shows that education on parenthood can considerably reduce the risk of infant developmental problems. Despite the many problems faced by adolescent parents, it seems some young mothers and their children are doing well. The success of adolescent parenthood relies on numerous factors, the key among which is support (from family, friends or the wider community), assistance and alternative care provided by another household member, fertility control as well as the opportunity to continue education. Self-esteem is another important factor for successful adolescent parenthood. The better the young mother feels about herself, the more inclined she will be towards her child. High levels or maternal depression and low levels of self-esteem entail additional parenthood problems. Despite theoretical differences in attempts to conceptualise the parent–infant relationship, there is agreement that the main component of successful parenting is parental sensitivity. Sensitive parental behaviour includes the ability to provide appropriate responses to children’s signals, especially the most important among them – crying. The parent has to be able to identify the child’s need, interpret it and respond to it in an appropriate and effective way. Emotionally mature couples who have children are usually successful in overcoming problems which are primarily linked to the adolescent age and the stressful events young people of that age are faced with. The ability of adolescents to be successful parents is therefore the subject of much research. Overwhelmed by issues related to their own physical, psychological and social development, adolescents often have difficulties dealing with themselves (predicated in large part on psycho-social problems). As such, their capability for “sensitive parenthood” may be reduced, which undoubtedly has long-lasting consequences on child development. In our study of adolescent mothers (compared to other mothers) during the war in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, we observed the following phenomena: 1. a lower level of basic knowledge on infant development and needs (which formula is the best, when should the child start sitting, walking and talking), which indicates a lower level of interest (emotional orientation) in the child; 2. greater frequency of emotional difficulties and lower frequency of depression; 3. lower frequency of establishing contact with the child (eye contact, smiling, gentle touches or initiating play); 4. lower frequency of infant attempts to establish contact; 5. shorter period of breastfeeding; 6. lower level of recognising infant signals (recognising the reasons for the child’s crying); 7. lower level of self-confidence and self-esteem; 8. greater frequency of perceiving child care as a heavy burden. These are given special attention and care within the psycho-social assistance programme.

| RISK GROUPS – SUMMARY: |

|---|

|

|---|

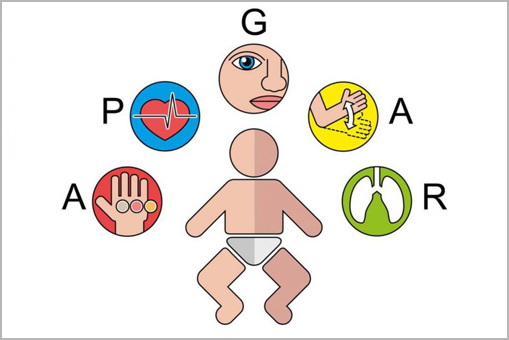

WARNING SIGNS

The maternal relationship with the child is already evident during pregnancy, so the frequency of gynaecological check-ups can be an indication of the future relationship with the newborn. A lack or the irregularity of medical check-ups during pregnancy is a significant indicator of future difficulties. The length of breastfeeding, and the regular prophylaxis of anaemia and rickets, also reflect the quality of the early mother–infant relationship, reducing the risk of neglect and other problems in the early relationship. For balanced mutual communication, it is important that the mother understands the messages conveyed by the infant, and understands and satisfies the needs they express. Mothers who have a higher degree of formal education and more knowledge of child development are more successful in establishing communication with their infants and are less likely to neglect them. Scarce communication between mother and infant (holding the infant, engaging in play, vocal communication, touch, exchange of emotion) can be a sign of a severe disturbance in the early relationship. Adolescent mothers (age <19) present an especially high-risk group, due to a considerably higher frequency of disturbances in communication with the infant, symptoms of neglect, lower levels of understanding infant needs and development (which milk is the best, when does the infant begin to sit, walk and talk?), absence of medical check-ups and administering vitamin D supplements, more frequent skin infections of their infants and irregular immunisation. Mothers who smoke are more likely to neglect personal hygiene, as well as the hygiene of their children and the rooms they inhabit, and often have husbands who are also neglectful of their hygiene. Children of smoking mothers often contract diseases of the respiratory tract. All this indicates that the mother’s smoking can be another indicator of disturbance in the early mother–infant relationship among research participants. Infant neglect reflects a severe disturbance in the early relationship between the mother and her infant. The most reliable indicators of this disturbance include neglect of maternal and/or infant hygiene, overprotection of the infant, inability to recognise why the infant is crying and failing to take the infant to preventive check-ups. Mothers belonging to this group frequently display PTSP symptoms, difficulties adjusting and becoming independent, emotional difficulties and a lack of self-esteem and self-confidence. This is commonly found among adolescent mothers. Their infants suffer from a lack of quality communication, irregular immunisation, vitamin D deficiency, anaemia, chronic diarrhoea, skin infections and frequent inflammations of the respiratory tract. This confirms the practical value of such indicators of early relationship disturbances in the everyday work of professionals who deal with small children and their parents. The presence of certain, easy-to-identify indicators should be a clear warning that the mother–infant relationship demands attention and that the causes of these disturbances should be examined.