How to stimulate communication between parent and infant, how to boost the development of attachment – Instructions for parents

Milivoj Jovančević

The programme has the following components: psychological support (child psychologist) – through group education about the basics of the early mother-child relationship and through individual work; encouragement of communication with the child through massage, medical developmental gymnastics and voice communication. The main tasks of the programme are as follows:

- To make sure that the mother feels protected

- To boost the mother’s budding sense of self-confidence and self-respect

- To instruct the mother about the basic needs and development of the child

- To instruct the mother to communicate with the child (breast-feeding as a way of communication, massage, developmental gymnastics – “Baby Fitness”, stimulation of voice communication – “Voice Fitness”, playing with the infant), where it is necessary to demonstrate the techniques of doing the exercises and to show the reward represented by a happy and pleased child.

1. Communication with the infant: breast-feeding and care

Breast-feeding is a very good way of communication between mother and child. Several levels of communication can be recognised in this act. The first is a message to the child – here it is warm, safe and comfortable, here there is food. Nature has balanced this relationship very wisely; first of all, the child is born with the sucking reflex – the child tries to put in his mouth anything that happens to be near the mouth or on the cheek and starts to suck; and secondly, children are in the oral phase, which means that the biggest pleasure and comfort comes through the mouth. On the second level of communication during breast-feeding, mother and child get to know (recognise) each other through touch, in the same way as they do during changing and bathing. The more they touch each other, the more talk and grimaces there are, and the better the communication. Naturally, there is also the sense of smell, which infallibly identifies the mother. During breast-feeding, the child experiences all the pleasures of this world: the sense of warmth, gentleness, safety, pleasant taste, the satisfaction of his hunger and the need to feel loved. On the other hand, the mother has the closest possible contact with the baby, in a connection which in a way resembles the days of pregnancy when she felt every move the child made and experienced it as part of herself, as part of her body. The mother feels the warmth of the child and the child’s movements, the mother feels that she is playing the role given to her by Mother Nature – she is successfully feeding and caring for her child. Finally, she has the feeling that she has done her biological duty – to produce offspring and to make sure the child grows up.

Sometimes the child is too agitated to begin to feed peacefully. You should then try to soothe the baby in a quiet, rhythmic voice. Try to use vowels by starting in a higher and ending in a lower pitch (e.g., a “downward“ long “a“). In contrast, if the child is sleepy, you can awaken her by more intense touching, louder baby-talk and by using “upward“ vowels. Observe your baby: when she is full, she will turn her head away from the breast for an instant, stretch her body backwards and then extend her little arms along her body. That is a message – I am full and happy, now I’m going to sleep.

Your baby is able to imitate grimaces and voices from the earliest age. Do try, and you will stimulate the development of communication and, indirectly, the psychomotor development of the child (sticking out the tongue, closing and opening the mouth, pressing lips together, closing and opening the eyes).

2. Communication with the infant: Baby Fitness

2.1. MASSAGE

Andrea Čalopek Butković

I FACIAL MASSAGE

- FOREHEAD

Place both thumbs on the baby’s forehead vertically. You should not cover the baby’s eyes, because babies feel insecure if their eyes are covered. Start at the centre of your baby’s forehead and slowly caress his skin outwards.

- NOSE, CHEEKS

With your thumbs alongside his nose, move your hands from the nose and ever so lightly across his cheeks. This massage is beneficial if the baby has a clogged nose because it serves to drain mucus from the nose, and the air passages become clear.

- CHIN

Place your thumbs at the centre of the chin. The movement starts from the centre and slowly progresses across the chin.

II HAND MASSAGE

- Place both hands on the baby’s shoulders. By slowly massaging the shoulders, descend down the upper arm and then to the lower arm. With the palms of your hands, you should try to cover as much of the arm surface as possible.

- We now massage only one arm. We use both our hands to take hold of the baby’s arm in the upper arm area. We slowly descend down to the lower arm and hand. We must use the whole palm, as if you are pulling on something lightly. You should not use the tips of your fingers, because that would not be comfortable for the baby. Do this several times with one arm, and then proceed with the other arm.

- We massage only one arm. With one hand we take hold of the baby’s hand and wrist. With the other hand we do the massage by encircling the baby’s arm, in the form of a ring. The movement starts in the upper arm area, descends down the lower arm, and ends at the hand. Do this several times, first on one arm, and then start with the massage on the other.

- We massage only one arm. Press the fingers of both hands together and place them on either side of the baby’s upper arm. Roll your hands from the upper arm, down the lower arm, all the way to the hand. Do this several times, first on one arm, and then on the other.

- If the baby’s hand is clasped into a fist, put the palm of your hand under the baby’s palm. With the fingers of your other hand, stroke the upper side of the baby’s fist. The movement starts on the baby’s fingers and continues to the wrist. After several repetitions, the baby should open up her hand and you achieve contact, “palm-on-palm” touch.

III CHEST MASSAGE

- Place both hands on the centre of the chest area. The movement, light strokes, proceeds to the shoulders, and then down the sides of the chest to the centre of the chest again. The movement is not interrupted, but proceeds in continuous circles. You should do 6-7 circles in a row.

IV STOMACH MASSAGE

- Place your hand on your baby’s navel. If you are right handed, then use your left hand. With your right hand you should apply light pressure and move your right hand clockwise, in a circular motion, from left to right. When you reach the position where your hands are side by side, you lift your right hand away from the tummy and proceed with a new cycle of motions. You should not lift off the hand on the baby’s navel. This direction is recommended because our alimentary tract works in that direction.

- The tummy can be massaged in a way that you press the fingers of your hand together and caress the tummy with the palms of your hands. The tummy is massaged by moving your hand from the upper tummy area downwards to the lower tummy area. When you reach the lower part with your hand, use the other hand to start the massage on the upper part of the tummy. Your hands alternate. Do 6-7 alternations in a single massage cycle.

V LEG MASSAGE

- Place both hands on the baby’s hip and upper leg. The stroking movement starts at the knee and proceeds to the lower leg and foot. Try to cover as much of the leg surface as possible with your palms.

- We massage one leg at a time. We use both hands to hold the baby’s leg in the upper leg area. Use the whole hand to hold the leg, not just the fingers. The movement starts at the upper leg and proceeds to the lower leg and foot as if you were pulling on something lightly. Take care that you do not use the tips of your fingers, because that is not comfortable for the baby. Repeat the massage on one leg several times, and then start massaging the other leg.

- We massage one leg at a time. With one hand we hold the baby’s leg in the ankle area. With the other we do the massage by encircling the baby’s leg, in the form of a ring. The movement starts at the upper leg and proceeds to the lower leg and ankle.

- We massage one leg at a time. Press the fingers of your hands together and place them on either side of the baby’s leg. Roll your baby’s leg between your hands from the upper leg down the lower leg all the way to the foot. Do this several times, first on one leg, then start rolling the other.

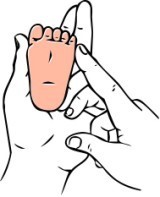

- Place your thumbs at the centre of the baby’s foot. The thumbs have to lie on the foot, with the thumb nails in the same direction as the baby’s toe nails. Stroke the foot from the centre outwards. Be sure that the thumbs are pressed against the foot. There are a number of nerve endings in the foot, so with each touch we stimulate a large number of nerve cells. That is why it is good to include the baby’s feet in the massage, so that the baby gets as many stimuli as possible. Do this several times, first on one foot, and then on the other.

- The feet can also be massaged horizontally. Place your thumb crossways on the lower part of the sole. Move the thumb from the lower part of the foot to the upper part near the toes. When you finish the movement on the upper part of the foot, start the same movement with the other thumb on the lower part of the foot. The thumbs alternate. Do this several times first on one foot, then on the other.

Do not forget the pressure pads on the underside of the toes. Be sure to massage them; you will improve the circulation in the baby’s feet.

- The whole hands can also be used to massage the baby’s feet. With one hand, hold the leg in the lower leg region for stability. Place the palm of your other hand on the foot and apply soft pressure on the foot. Remove the palm from the foot and repeat this several times..

VI BACK MASSAGE

- The baby should lie on her tummy for this massage. The massage is divided into three parts: you first massage the top, then the middle, and in the end the small of the back and the bottom. Place your hands at the centre of your baby’s back and make outward strokes.

You first repeat this several times on one part of the back and then move on to the next.

- A back massage may also be done when the baby is lying in her mother’s lap. One hand is placed on the baby’s bottom, and the other hand does the horizontal stroking movements. The stroking movement begins on the shoulders and ends on the bottom, where the hands meet. It is important to point out that the hand should be shaped to follow the contours of the baby’s back.

- The position of the baby is the same as in the previous massage. One hand is placed on the baby’s feet, and the other is used to make horizontal stroking movements. The stroking movement begins on the shoulders and ends on the bottom. The hand should be shaped to follow the contours of the baby’s back.

- If you do the massage in the described order, it is proposed that you finish the massage with this exercise. The baby is on her tummy.

You move your hand from the top of the back to the lower back. When you reach the small of the back with the palm of your hand, you use the other hand to begin the massage on the top of the back. The hands alternate.

2.2. MEDICAL DEVELOPMENTAL GYMNASTICS

Milivoj Jovančević, Andrea Čalopek Butković

The exercises below have multiple benefits. The child is born, but the brain is still developing. Millions of nerve cells are created which travel to their destinations and establish connections with other brain cells. By exercising, we stimulate the central nervous system and accelerate this process. We may observe how the brain works, and thus the effects of our activities, through the psychomotor and emotional development of the child. It is recommended to do these exercises twice a day for some twenty minutes, and only when the child is in a good mood.

So many times have we experienced the pleasure of exercising with our infant and the abundance of warm feelings that are born and shared through this experience. Exercise creates a closeness surpassed only by the intimacy of nursing your baby. The mother familiarises the child with her touch, she gets to know her baby’s soft and warm hands, she becomes familiar with the scent of her child, and the sounds and emotions that the baby uses in response to her expressions of love and attention.

In some cases, due to difficulties in their own lives, mothers have difficulties accepting their newborn child. Exercising with the baby is such a powerful and motivating experience that it mobilises all the mother’s senses and feelings, soon establishing a normal relationship, and the communication that is necessary for the healthy growth and development of the child. It removes the mother’s fears and insecurities and opens up space for enjoyment and expressions of love. Therefore, we recommend that in doing each exercise you let your feelings and the exchange of messages flow freely. Gently touch the baby’s skin over the entire body, coo, sing, smile and kiss… You have a unique opportunity to experience, perhaps, the happiest moments in your life – take it, and enjoy.

| No. | FROM THE | DESCRIPTION OF THE EXERCISE |

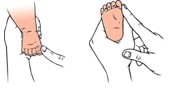

| 1 | 1st month | Very often, the position in the uterus causes the feet to turn inwards (the soles “stare” at one another).

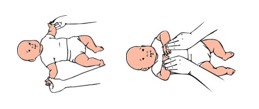

The baby is lying on her back. Bend the leg at the hip and the knee. Clasp the baby’s ankle with the thumb and index finger (as if between scissor blades), the palm facing upward and outward. With the other hand, stimulate the outer border of the foot from the toes towards the heel. By reflex, the foot will turn towards its outer border (towards the finger that is stimulating it). |

| 2 | On some occasions, the pressure of the uterine wall causes the foot to turn upwards, so that the instep nearly touches the shin, while the heel bone very prominently sticks downwards.

The child is in the same position as in Exercise 1. With one hand, clasp the child’s foot around the ankle (“scissors”). The palm or the fingers of the other hand are placed on the top of the foot and the foot is pressed downwards. |

|

| 3

|

|

Sometimes only the front part of the foot was pressed against the uterine wall, so that the baby’s foot seen from the bottom looks like a banana (the front part of the foot looks inwards).

The child is in the same position as in Exercise 1. Clasp the heel with one hand (the pictures show 2 ways of holding the heel fixed), and push the front part of the foot outwards with the other hand. |

| 3a | The infant’s head might be “flat” on one side and there might be an injury to the neck muscles (positional torticollis)

Fix the shoulders on the surface with one hand and rotate the head left and right as far as it goes. Then, with the baby facing you, flex the head towards the left and right shoulder. |

|

| 4 |

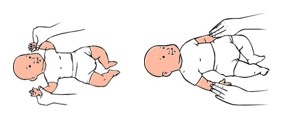

The child is in the same position as in Exercise 1. The soles are pressed on the surface. Clasp the baby’s shins and feet. Lower the soles onto the surface and lift them up again. |

|

| 5 |

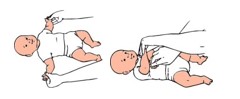

The child is lying on the back. Clasp the legs in the area around the knees and press the child’s knees towards the tummy, then stretch the legs out on the surface. |

|

| 6 |  The same as Exercise 5, but performed with alternate legs; one leg is bent while the other is simultaneously stretched out on the surface (asymmetrically). The same as Exercise 5, but performed with alternate legs; one leg is bent while the other is simultaneously stretched out on the surface (asymmetrically). |

|

| 7 |  Hip exercises Hip exercises

The child is lying on the back. The legs are bent at the hips and knees. Clasp the knees and shins and stretch them out to opposite sides. When the legs are stretched to the sides, try keeping the knees up at the level of the hips, and press the knees downwards as far as possible towards the surface! |

|

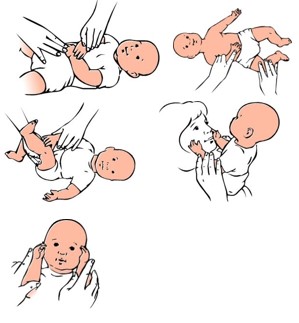

| 8 |

The child is lying on the back. Try keeping the baby’s upper arms horizontal to the surface. Hold the baby’s palms and move the forearms up to the elbows: bend (hands go towards the chest) and then stretch, that is, return the hands to the initial position on the surface. |

|

| 9 |

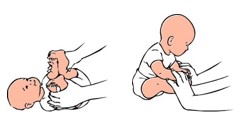

The child is lying on the back. The arms are in a horizontal position, stretched out from the body. Cross the arms on the chest (left hand on right shoulder, right hand on left shoulder), then return to initial position |

|

| 10 |

The child is lying on the back, with her arms beside the body. Lift both arms stretched above the head, and return to the initial position on the surface. |

|

| 11 |

The same as Exercise 10, but with alternate arms; while one arm is above the head, the other is lying parallel to the body |

|

| 12 |

Open the child’s palm with the thumb of one hand. Hold the child’s fingers with your thumb to keep the palm open, and use the thumb of your other hand to rub (stroke) the baby’s palm. |

|

| 13 | Use the child’s palm to go over her forearms, tummy, one leg then the other leg, her own face and then the mother’s face.

Position the child on the tummy.

Open the palm on a smooth and tight surface that will not bring on the baby’s grasp reflex. |

|

| 14 | 2nd month | Position the child on the tummy. Place the forearms under the chest, close to the body.

Bend one leg at the hip and knee and place it under the tummy. Also bend the other leg, but place it lower down from the first leg. Alternate the legs as if the child was crawling. If the child tries to push, support the foot with the palm of your hand. |

| 15 |

Turn the child from the position on her tummy to her back, and then again to her tummy. Bring the child to lie on her side in a balancing position, leaning on the lower arm. Try to encourage the baby to turn (tummy – back, back – tummy). Help with your hand, and by calling to the baby so that she turns her head, and through this, the entire body. |

|

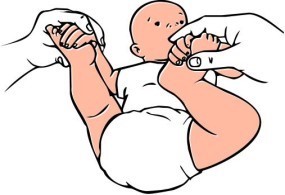

| 16 | 3rd month |

The baby is lying on her back. Clasp together the shin and forearm of the child and bring the child to a sitting position rotating her sideways. When in the sitting position, gently tilt the baby in all directions to exercise control of the head (Buddha position). It may also be performed by holding the child by the shoulders while you raise her into the sitting position. |

| 17 | 4th month |  The baby is lying on the back. The baby is lying on the back.

Take the child’s hands and make them touch her feet. When she grasps the feet, bring them both towards the child’s face. |

| 18 | 5th month |

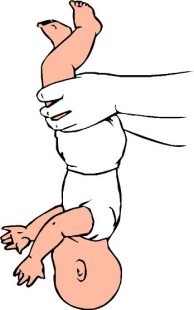

The child is lying on the back. Take the child by both thighs and lift from the surface (the child hangs head down). Let the child press with her hands on the surface or gently lean her head on the surface; later you may perform a full turn until the child lies on her chest. |

| 19 |

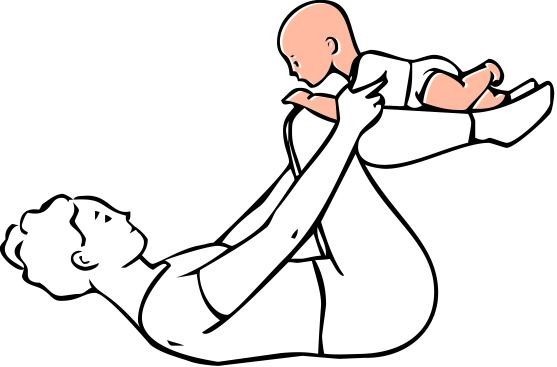

“Airplane” The parent is lying on her back with her legs bent at the hips and knees, and the shins parallel to the floor. The child lies on her tummy on the parent’s shins (as if flying). |

|

| 20 | 6th month |

Sideways sitting position The child is lying on the side. The leg she is lying on is bent upwards towards the tummy, and the other leg is placed over it with the sole of the foot on the surface. Pull the child by the top arm until the baby leans on the bottom forearm. |

| 21 |

Crawling, position on all fours. This is performed by a stronger rotation of the body to the side. Hold the knees under the body, that is, under the pelvis; do not let them go sideways as in a frog. |

|

| 22 | 7th month | Position on all fours.

Lift the pelvis from the surface, place the knees under the body, simultaneously making sure that the arms are under the chest. In the beginning, support will be provided by the forearms, and later just by the hands. Position on all fours. Let the baby support herself with her arms (forearms or hands), and simultaneously lift both stretched legs (as if playing “wheelbarrow”). |

| 23 | 8th month |

Sitting on heels supported by your hands at the front. Slightly raise the baby’s bottom and rock left and right (stimulate rotations of the body by putting objects on the sides). |

| 24 |

The child is in a sitting position. Spread her legs to give broader support for stable sitting. |

|

| 25 | 10th month |

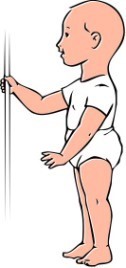

Place the child from a sitting to a standing and kneeling position. |

| 26 | 11th month |  Place the child from a standing/kneeling position into a Place the child from a standing/kneeling position into a

stride while she holds herself up. |

| 27 | 12th month |

From stride position to standing position. |

2.3. STIMULATING SPEECH AND LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT (VOICE FITNESS)

Mirjana Lasan

Speech and language represent a kind of foundation for development. Language is needed for communication and for expressing thoughts, and it is widely known that good-quality and efficient communication has an impact on an individual’s social and emotional wellbeing. In the same way, the combination and mutual influence of environmental and birth factors affect the development of speech and language, in other words, communication.

Speech development does not begin with the first word – around the first birthday – but much before that. Some believe that it begins immediately after the child is born, with her first cry, and when the child begins to breathe independently. However, many people believe that it begins even earlier, in the prenatal period, when the internal ear has developed, and, with it, the ability to hear. Vocalisation is the main precondition for speech, and in the first year of life, the child produces a range of vocal sounds that are crucial for the later development of speech. We

often tend to ignore these sounds, by describing them as “just babble”, not thinking that these very sounds may provide a lot of information about a child’s development.

Hearing, listening and paying attention are important prerogatives for the development of speech and language. Right after they are born, children will react with fear to very loud sounds. The attention span in the first weeks is very limited, but, soon after, babies will begin to listen when someone talks to them, and they will react with a glance and a smile. They will begin to show interest in the movement of the lips of the person talking to them; they will quieten down when they hear the voice of a parent, and turn their heads towards its source. As the weeks go by, children will be able to listen, observe and differentiate among the increasingly complex and fine sounds and activities in general.

The interaction between the infant and the mother is to the greatest extent an emotional one. It has also been proven that babies show the greatest interest in faces and voices from the earliest age. Besides being interested, children are also very sensitive to voices and adjust to them easily, especially to the mother’s voice or to the voice of the person who cares for her the most. Precisely for this reason, children will more readily react to human communication by imitating the expressions of the faces and the sounds or voices. However, the main precondition for imitation is motivation, or the wish to communicate with others. There are many games to help this process, such as hiding the face between the hands, or a tickling game, because it is well known that children learn best and most easily thorough play and experience.

Through games, or another type of interaction, we develop communication skills that go beyond verbal expression. Thus, for example, eye contact and pauses in communication that give the child time to respond represent important non-verbal communication skills. At the same time, they enable the parents to monitor the child’s abilities and speech development as a whole.

Children also react to the intonation of the voice of the person talking to them. Grown-ups often talk to a small child in a prominently high-pitched voice to attract and keep her attention. After that, they will make a pause which allows the child to respond with a glance, a smile or by making vocal sounds.

The sounds that the child can produce are closely related to the anatomical structures that develop over time. With the growth of the child’s head and neck, over a period of several weeks and months, the child will be able to produce various kinds of sounds.

Most newborn babies use their voice to cry, but also to produce a few other sounds. In the first eight weeks, they sigh, sob, moan when they feel uncomfortable, they produce short squeals and sounds that resemble the vowels “a”, “e” and “o”. In the beginning, these sounds are mostly an introduction to crying, but as the child matures, they increasingly become associated with pleasure. At about 8 weeks, babies begin to coo, which is the most frequent reaction to friendly voices and faces. At about 2-3 months they are able to

vocalise two to three syllables, for example “aah-caa”, etc. At around 4 months babies begin to experiment with their speech organs, and so, during that period, the consonants “b”, “p”, “t” and “d” can also be heard. With the development of their motor skills, some time around the 6th month of age, the baby begins to babble, and syllables such as “mamama”, “dududu” or “papapa” are not unusual. In this period, the imitation game between child and adult also helps the further speech-language development. When they are about 7 months old, children are able to vary the pitch and loudness of their voice, so that at 8 months they produce sounds related to a game. At around 9 months, children begin to combine different consonants and vowels, but also to produce some new consonants. Then, the children begin to use these combinations with a specific purpose and meaning, which will lead to the first words that grown-ups understand.

So, communication skills begin to develop at birth, and, as children get older, and their motor readiness develops, these skills grow more complex. Besides encouraging them, it is very important to pay attention and observe what sounds children produce and how they do it, which will allow for the timely identification of possible warning signs.

Taken from “Children’s communication skills”, B. Buckley (2003)

| Communication skills of a three-monthold baby

• Cries • Smiles at people, toys • Looks at people, toys • Makes eye contact • Makes vowel-type sounds • Coos and gurgles • Startles in response to loud, sudden noises • Responds to speech by looking at the speaker’s face |

Warning signs

• Does not smile • Does not vocalise • Does not cry when hungry or in pain • Never turns head towards the source of sound |

| Communication skills of a 6-month-old baby

• Appears to understand tones of warning, anger and friendliness in voices • Recognises own name • Seems to recognise names of family members • Produces some consonants • Participates in turn-taking games and “question and answer” games • Looks at what an adult is looking at |

Warning signs

• Does not look at the speaker • Does not follow moving object with eyes • Does not babble by using consonants and vowels (for example, ma, boo, go) • Mostly silent apart from crying. |

| Communication skills of a 9-month-old baby

• Stops an activity when her name is called • Looks towards speaker who calls her name • Stops activity in response to “no” • Babbles by combining different vowels, varying pitch and loudness • Points and vocalises to request things • Performs routine activities on request (for example, waves “bye-bye”) |

Warning signs

• Not interested in socially interactive games • Does not recognise own name • Does not produce many sounds • Does not produce a range of syllables (for example, mamama, bababa) • Not interested in sound-making toys |

| Communication skills of a 12-month-old baby

• Responds appropriately to some verbal requests • Makes appropriate verbal responses to some requests (for example, says “bye-bye”) • “Talks” to people and toys by combining a few syllables that vary in pitch and intensity of voice • Vocalises in response to being spoken to • Combines looking, gesture and vocalisation to make requests or to protest |

Warning signs

• Does not recognise familiar objects when named • Does not turn her head towards a person calling her name • Does not produce many different syllables • Does not look towards the place where the finger points |

Some exercises are listed below for adults to encourage, and at the same time monitor, the speech-language development of the child. It is important to mention that it is best to perform the exercises in the position that is most comfortable for the child, but it is essential that eye contact is maintained. It is also desirable to pause after each exercise to allow the child to respond, thus helping you to monitor the child’s answers and her development.

- Alternate opening wide and closing the mouth

- Alternate opening the mouth wide and stretching it into a smile

- Pursing the lips

- Giving kisses that might be both loud and quiet, one or several in a row

- Sticking the tongue out and pulling it in

- Whistling from loud to quiet, from high-pitched tones to lower ones, in fast and slow rhythm

- Sighing by producing the vowel “aah” which may also be louder or softer, high or low pitched, and slower or faster

- Moaning accompanied by the vowel “e” which can also be varied as in point 7

- Brief squeaking, accompanied by the vowel “o” (vary as in points 7 and 8)

- Gurgling

- Cooing (caa, coo, cor, kii, etc.)

- Babbling (baa, po, ma, nu, etc.)

- Cooing by producing a row of syllables (cacaca, cococo, cucucu, later gagaga, gugugu, ghighighi)

- Babbling by producing a row of syllables (bababa, bobobo, pupupu, papapa, mememe, nenene, etc.)

- Imitating the child by using the same sounds as the child and a normal speech intonation.

These exercises may be done relatively frequently, depending on how often the child “allows” it. Regardless of how many times they are performed, children love the attention of grown-ups, either through singing, playing or any kind of interaction.

2.4. Play with your children

Mirjana Šprajc Bilen

ENJOY THE GAME AND THE CHILD

REMEMBER, YOU WERE A CHILD YOURSELF

In the same way in which a baby needs food and care, she also needs someone to gently touch her and talk to her, she needs to enjoy playing with her parents, and all this from the earliest age. Do not wait for the baby to grow up and become an ”equal” partner in the game.

Both you and your baby will benefit from playing together. You will enjoy seeing your child learn new things, you will look forward to the togetherness and intimacy, because it is widely known that enjoying things together makes people feel closer. The child will grow up with confidence and trust in you and those around her, which will help her grow into a happy child.

Children who get more attention from their parents show better progress in their psychomotor development.

Playing with your child is a clear sign of care and love, and this is a sign that the child will always interpret as love. And love is the most important ingredient of growing up. If you do not have time for your child, she will think that you do not love her, because she will notice that you do have time and patience for things that you care about.

GAMES FROM BIRTH TO 12 MONTHS

When a baby is awake she needs a pastime and encouragement. This is why we surround her with rattles, mobiles and other toys. The younger the baby, the faster she becomes bored with one game and seeks new pastimes. Playing with mum and dad is much more interesting for her.

In the first months, too much noise should be avoided, since laud laughs and sudden gestures may upset the child. Children of that age prefer observation games, they want to communicate with their parents face to face, and see the response in their parents’ faces. When talking to a baby, the parent must be careful not to do it for too long, not to talk without stopping and thus irritate the baby.

The mother and the baby are having a dialogue: the mother says something and the baby looks and listens. After that, the roles change: the baby coos, but also tries to express herself with her arms, legs and the entire body. Then it is the mother’s turn again. It is from this first dialogue that the communication of the child with her surrounding begins. If the child has learned to “wait her turn” here, she will also know how to do it later on.

Energetic games

- Give an opportunity to your child to become aware of her body; blow on her tummy several times in a row, “walk” with your finger along the entire length of her arms, count her fingers and gently tickle her.

- You can place a baby who is older than one month on her chest for a few minutes. This is a good exercise to strengthen the neck and shoulders and gives you the opportunity to position yourself with your face in front of the baby’s and have a brief “conversation” with her. (Never leave the baby alone in this position!).

- When the baby is a bit stronger, put her in your lap. Let her “stand” on her feet while you hold her arms, or let her “fly” in your lap while you hold her firmly. (The baby is standing or kneeling in the parent’s lap. Holding the child firmly by the hands, the parent moves his or her thighs left and right giving the impression that the child is “flying” or dancing).

- Exercise together. While the baby is lying on her back on the floor, gently raise her shoulders one by one towards the baby’s head; then allow the baby to press her soles into your hands, or gently “ride a bicycle” with her legs.

- Enhance physical skills with toys that she can squash, shake, press or turn, which will stimulate control of the hands; give the baby toys that roll, which will encourage her to crawl (try to have a crawling competition). If possible, arrange the furniture in such a way that the child can walk around the whole room by holding herself up.

- Let the baby “swim” in the tub, both on her chest and her back (always support her head and shoulders with your forearm). Or take a shower together, and let the baby feel the water on her head. Never, not even for a moment, leave the baby out of sight when she is in the water!

- In the park, pass the baby a ball while she is sitting down; swing her on a swing.

Creative games

- Talk gently to your newborn baby and look her in the eyes. Try some early games, such as sticking out your tongue and laughing, and see whether the baby responds.

- Sit the baby on your knee and gently sing lively, rhythmical songs, which will stimulate speech development.

- Provide new stimulating experiences. A newborn infant likes to watch moving objects (for example, mobiles), while an older baby likes to bang toys on a surface and explore different objects and materials.

- Play games that require specific actions from your baby. Observe whether your one-month-old baby can follow a slowly moving object with her eyes, or if your 9-month-old baby can find a toy if you hide it under a piece of paper, or if a 12-month-old can give you a toy if you ask for it.

- Help the baby to gain a feeling of identity and to experience herself as a person, by giving her a chance to see herself in the mirror, to look at pictures of other babies, and, when she is bigger, teach her to point to different parts of the body.

Popular games

- Throwing. All babies throw their toys. Turn this into a game, and let her throw the toys onto different surfaces, such as sand or leaves to produce different sounds.

- Hide and seek. Hide so that the baby can see only part of you, or hide a teddy bear under a pillow and let the baby look for it.

- Emptying. Place a few toys into an old handbag and allow the baby to take them out. Or let the baby explore the kitchen cupboard which you have filled with plastic bottles, strainers and sponges.

- Pushing and banging. Give the baby a cardboard box that she can fill with objects and push around. Let her bang on a frying pan with a wooden spoon.

- Early construction games. Make a tower out of two or three blocks (first soft ones, and later wooden ones) and let the baby strike it down. Then teach her how to build it up again.

- Place the baby on a towel. Take some pleasant warm oil (such as wheat- germ oil) and gently massage the baby, starting from the centre of her body. Avoid the area around the navel in newborns.

- Leaf through books together. In the beginning, books made of cloth are best, and after the baby turns 6 months, simple cardboard books which can even be wiped with a wet cloth.

- Describe to the baby what happened during the day, or listen to some relaxing music together and rock the baby to the rhythm of the music.

FROM 1 – 2 YEARS

- Put on some nice music and dance with your baby. When the baby is tired, put on some quiet music and gently “slide” around the room.

- Touch your nose and let the baby touch hers, shake your shoulders and let the baby do the same, tap your feet and let the baby imitate you. Then see if the baby can follow you doing all three activities in a row.

- Be “funny”. Use “funny” steps to walk around the room, waddle around the kitchen, turn around three times, touch the tips of your toes and, finally, run back to the sitting room.

- Ask your baby to move her shoulders until you say “Stop!” If the child can already say “stop”, exchange roles. (This skill in responding to “stop” is useful to avoid danger when you are out of the house).

- Go over and through a simple course of hurdles. Arrange cushions around the room, for the baby to climb over, cardboard boxes to crawl through, and a

table to crawl under (first check that the child cannot hurt herself). You can also let her crawl down and under your knees.

- Sing as many lively and rhythmic songs as possible.

- In the park, give the child toys and objects to push and pull, encourage her to walk (later on to run) from you to your partner, gradually increasing the distance. Partially hide behind a tree and let the child look for you, feed pigeons and other animals.

Creative games

- Put some lukewarm water in a bowl and let the child experiment by pouring water in and out of different containers. One container may have a large hole, and the other several small ones. Add some ping-pong balls for the child to push. (Never leave the child alone near water or in the water!)

- Fill a container with clean sand and let the child pass it through a sieve and through a funnel. Add some water so that she can make mud pies. (Be careful that she does not put sand in her mouth!)

- Show the child how to make plasticine sausages, or balls, cakes or other shapes.

- Let the child draw on paper with coloured crayons, washable paints, or finger paints. Children like to make colourful footprints or handprints. Different shapes can be made out of vegetables, such as potatoes, which can be dipped in paint and used as stamps. Do not give a child a pencil or pen with a sharp point!

Popular games

- Hide and seek. This is an ever popular game and can be made even more interesting if, for example, you hide a toy under a plastic bowl and place another two bowls beside it. Ask the child to tell you under which bowl the toy is hidden.

- Sorting game. Play the game of finding objects, the “find me” game. When the child finds an object you have named (let us say it is an apple) ask the child to find another apple. Continue with questions: “Can you find the cow, bus, doll, etc. The objective of the game is to sort objects into groups, for example, animals, fruit, dolls, etc.

- Acting. Pretend that you are drinking tea with your child, or that you are treating a small teddy bear by putting a plaster on its knee.

- Fetching. Give the child a small basket or bag and ask her to fetch you different things. Start with one thing in the same room, such as a plastic cup, and then ask her to fetch a sponge, a plastic plate, etc., from different rooms in the house.

- A small child learns to speak by listening to the same words again and again. Therefore, hug your child and start the following game: show, for example, a table and say: “This is a table”, then point at a chair and say “This is…” encouraging the child to finish the sentence if she is able to. If you know that the

child knows the word, say something wrong on purpose to give her the chance to enjoy correcting you.

- Act out well-known stories and rhymes using rag dolls, or draw the characters on your fingers. You can also act out an everyday event such as bathing or going to bed by putting the dolls to bed and asking the child to be quiet and to avoid waking them up.

- Enjoy “quiet” activities. Help the child do simple jigsaw puzzles, construct a simple “building” from blocks, or just open up an old toy to explore what is inside. When you are showing the child what to do, keep your voice calm and create a peaceful mood.

- Leaf through books in the evening before going to bed and use them to stimulate a conversation about the child’s own experiences. Allow the child to help you hold the book and turn the pages.

WINTER GAMES

INDOORS

“Jump” into the bathtub with the baby at any time of day. This is against all rules, and is good for creating a feeling of closeness. Explore the water by splashing, or use plastic cups, bottles and other objects suitable for water games.

Sit in front of the mirror with your baby and look at “the other baby” in the mirror; bring the baby close to the mirror and let her touch the other baby with her nose, or give her a kiss. Or, first move either yourself or the child, or both of you, to the side of the mirror and then slowly appear. Your baby will rejoice every time her new “friend” appears.

Cut out pieces of old clothes of different texture (denim, corduroy, cloth, etc.). Make sure the pieces are big enough so that the baby cannot swallow them, that there are no buttons and that the pieces are clean. Explore these various materials by touching them with the child’s hands and face.

Hide and seek. When the child starts to walk, vary the peek-a-boo game. Hide under the bed, and, when the child comes near, come out. Or hide a favourite toy and congratulate her when she finds it.

OUTDOORS

In a restaurant, sit the child so that she can watch people in the street and the other part of the room.

Socialise with other mothers in the neighbourhood.

In shopping centres, you do not always have to spend money. Nowadays, there are shopping centres with children’s playrooms.

Swimming is ideal if you have the opportunity.

FINALLY, FOR CHILDREN OF ALL AGES:

DO NOT FORGET, FOR YOUR CHILD YOU ARE ALWAYS THE MOST POPULAR, THE MOST IMPORTANT, AND THE MOST INTERESTING GAME.

HOW TO CHOOSE A GOOD TOY

Mirjana Šprajc Bilen

A toy must be appropriate for the child in terms of her psychological and physical development. When selecting a toy, think about the child’s health, motor skills, intelligence, temperament and, primarily, about her age.

A good toy is one that the child likes playing with, which she can use in different ways, and which she always goes back to. Adults are usually disappointed if they buy an expensive toy that they like, but which the child does not accept and will not play with. This can happen if the child is not mature enough for such a toy, such as the case of a father buying an electric train set (which he wanted and did not have when he was little) for his three-year-old, while the son wants a bucket and spade.

If the toy is so precious that grown-ups restrain the child from playing with it (“Careful not to break it, or dirty it!”), it would be better not to have bought it, because, in such a case, the child cannot put it to use. When buying a toy, you must remember that the child does not care about its material value, as is the case with grown-ups. A child needs a toy that she can play with when she wants to, and in the way she finds suitable. This may sometimes imply that a curious child will take apart even the most expensive toy to explore what is inside, and after that she will show no more interest in it. Adults must know that this represents normal childlike curiosity and the child does not deserve to be told off for it.

It may often happen that a cheap, plain toy, for instance a stuffed bear, bunny or doll, becomes a favourite toy. The child becomes faithful and emotionally attached to it and keeps it throughout her childhood, until she reaches adulthood. Such a toy becomes precious to her. In such a case, it becomes more than a toy; it is regarded as a friend and life companion.

What is important when selecting a toy

The general rule here is that the toy must be appropriate for the child, her degree of psychological and physical development, which is most often proportionate to

the child’s age. Thus, the age of the child is a satisfactory criterion to bear in mind when selecting a toy. Besides the age, some other circumstances in the life of the child must also be taken into account, such as, for instance, the child’s health (a healthier child will have more energy for games and sports), motor skills (good motor control allows for more active play), intelligence (at all ages, brighter children are more creative and entrepreneurial, and their interest in games is more balanced), temperament, etc. Many children like movement and sports, so that sport accessories, such as a racquet or a ball will always come in handy, while a quiet child who, for example, enjoys drawing will be happy to receive a box of coloured pencils or some other drawing supplies.

When choosing a toy, it is good to know what the child has already got. Some children are so well equipped with toys that it is impossible to buy them something they do not already have. In that case, building blocks could be a good choice because they can be easily combined with existing blocks.

What a good toy should look like

Shape: The most important thing is for the toy to be shaped so that the child cannot hurt herself. There should be no sharp or hard edges, and all the parts must be well fastened. Besides, it is important for the toy to be pleasing to the eye in order to develop a feeling for aesthetics from an early age.

Colours: clear, bright colours, paints that are resistant to dampness and flaking, and entirely non-toxic.

Type of material: various materials are possible: smooth wood or plastics, but also soft, stuffed shapes and dolls that do not shed hair (teddy bear, bunny, etc.).

Dimensions: large enough for the child not to swallow it or stuff it up the nose.

The right toy at the right time

During the first year of life, toys must be simple, light, soft, brightly coloured, big enough and made of material that can be easily washed or disinfected. These are, for instance, rattles, small rubber dolls or animals that produce sounds when pressed, different mobiles – colourful shapes hanging within the child’s view and which move with the air currents – or rubber rings that children like to bite when they are teething. In the second half of their first year, appropriate toys are those that may be stacked or nested (blocks or plastic cups), cups, spoons, soft cloth or rubber balls with a slightly rough surface, various animals that float in the water, etc.

In the period from the first to the second year there is a great need to move around and explore the environment. Therefore, children particularly enjoy toys that allow them to do so. They like toys that they can push or pull along on a string, or those that they can ride (rocking horses) and thus develop nimbleness. They enjoy playing in the sand, so they need accessories such as buckets, spades, and other containers. At this age, they already like to build and construct

with various blocks which may be solid or hollow, and with which they will certainly like to play when they are older, but in different ways. While at this age they will just move the blocks around and stack them, later on they will construct tunnels and towers, and finally, entire buildings, houses, garages and cars.

From the second to the fourth year, children are attracted by tricycles and sledges, but also by all the toys they can use in the sand. Children usually like to draw and colour using large pencils, felt-tip pens and chalk. They can use scissors with a rounded tip. They like Lego bricks of larger dimensions, simple jigsaw puzzles, blocks with numbers and letters, simple musical instruments, abacuses with large balls, peg boards, simple card games and other society games, toys that can be wound up and cars of all makes and sizes. At this age, children increasingly play with other children, they begin to fantasise and imitate, and they show their imagination by playing different roles, such as mum and dad, a shop assistant, doctor, etc. For this, they need doctors’ or hairdressers’ equipment, dolls’ accessories, etc.

Educational guidelines for carers and parents

HOW TO BE A GOOD PARENT

Mirjana Šprajc Bilen

In bringing up a child, parents often start from themselves and their own wishes, and not from the child and her feelings, needs, capacities and abilities. Think for a moment: do you accept your child with all her virtues and faults, do you give her enough space to express her individuality, or are you too demanding, too strict, or perhaps too lenient, or inconsistent? What is your educational attitude to the child?

The most important feature of any family is the warmth of emotional relationships between parents and children, the emotional climate that reigns in the family. It has a strong effect on the children’s development, on their experience of relationships between people in general, as well as on their ability to bring up their own children when they become parents. The quality of the parent-child relationship depends of the characteristics of the parents, but also of the child who has an active role in this relationship from as early as birth.

Children differ among themselves, and some differences are largely innate, and cannot be changed through upbringing. Thus, parents with two or more children often wonder why they always have problems with one child, when they have brought up the others with no great effort, or why something that produces good results in one child, has no effect, or even the opposite effect, in the other.

Differences in children’s characteristics, such as physical appearance, temperament, gender, health, ability to adjust, etc., lead the parents to have a different relationship towards each child. Some children are “easy” to bring up right from birth; they eat well, sleep well, are healthy and have a friendly disposition, while others might be irritable, whiny, have their own eating and sleeping rhythm that the mother cannot “grasp”, and behave in an obstinate way. The mothers of such children quickly become tired, disappointed and irritable, they begin to doubt whether they are good mothers, which is often reinforced by the lack of understanding of the people around them (“Your child is always crying!”).

There is no recipe on how to be a perfect parent, and your child does not need a perfect parent. Children need parents who love them, but also who guide them, who show them that they are “in charge” of the relationship, who decide and take responsibility for the children, in the same way that the children take responsibility for tasks they are mature enough to do. If parents are consistent and patient, they win the child’s trust, which will be the source from which the child develops self-confidence and confidence in her qualities, and later on, in other people. This is an important precondition for the children’s development into mature and responsible adults.

How do we know if we are good parents? If the child has no significant problems in her development and in growing up.

Do you accept your child?

The most important thing is to show love to children and to accept them “as they are”. For example, it is not a good idea to expect a lively child to be calm, or a shy and cautious one to be open and quick.

Insufficient emotional interest in the child, a cold attitude and one where the child is ignored can derive from sentiments ranging from indifference to aversion. It is difficult for any child to stand the lack of parental love. Children experience this absence even when the parents love them, but are not able to show love. This may happen in the situation when parents love their children, but are too busy and do not have time for the children, when they are overburdened with troubles and problems, and although they care about the children, the children always have the feeling that the parents’ thoughts are somewhere else and that their parents are not really interested in what is going on.

Sometimes, parents will do anything to please their children, but they keep their distance: unfamiliar people look after the children, and the children spend their weekends and holidays with relatives. Often, even without a pressing need, a child might be left with her grandparents for years. If this long-term separation occurs in the first years of life, when the child returns home there is little chance for the necessary closeness and trust between child and parent to be established. An emotional contact can no longer be formed. During the separation, the child experiences parental rejection. In such a situation, children do not feel loved and sense they are to blame for the lack of parental love, since they feel they do not deserve it (they are not good enough, successful enough, obedient, clever or beautiful enough). In this way, children form a bad image of themselves and their abilities, they become insecure and develop the urge to “fight for” parental love, drawing attention to themselves through different forms of maladjusted behaviour (tantrums, aggression, refusing food, refusing to talk, etc.). If this does not help, they often either become extremely aggressive or they withdraw and isolate themselves. From the parents’ perspective, there may be various causes for them not to accept their children, and it is believed that they are not aware of most of these causes:

– parents imitate their own parents who did not accept them

– the animosity and anger towards their own parents is transferred onto their children

– they recognise their own faults in the children

– a parent may show hostility to a child in order to hurt the other parent, which is often the case with divorced parents.

Inconsistency in education: “Let her do whatever she wants, I’m tired!”

Educational inconsistencies often occur with mothers who are too busy and continuously tired, who have neither the patience nor the time for the child, and whose mood fluctuates. Sometimes they will punish their children for behaviours which would otherwise not be punished, and at another time they will let them do whatever they like, even things that they would not otherwise get away with, in order for the mother to be able to rest or do a task undisturbed. Some fathers, preoccupied with their work, let children do whatever they like, until they overstep the mark. On some occasions, they often severely punish their children for next to nothing. Based on such behaviour, it is difficult for children to know and learn what they can and what they cannot do; so, they become confused and insecure, afraid because they do not know whether they are loved. Children protect themselves from such feelings and insecurities in different ways, often through disruptive behaviour and neurotic reactions.

No one is always consistent. A child will understand some parental inconsistency and the sporadic unfair treatment if the parent admits it and does not blame the child for his or her own mistakes.

An inconsistent attitude may also be related to the conflicting attitudes of the mother and the father about bringing up their children. Children can adjust to this, too, if the parents admit their differences. What disturbs children is that the parents get into a conflict over these differences, rather than the fact that their parents have different views.

If one parent does not let a child do something, and the other allows her to, it is understandable that the children will favour the more lenient parent, but at the same time, she will lose confidence in both parents. This is the most frequent consequence of conflicting educational positions.

Unrealistic parental expectations: “He will be the best!”

Some parents expect their children to be successful in everything, to be the best and to develop in conformity with their set plan.

Such parents continuously advise their children, they direct them and make demands, and if the children do not meet their demands or expectations, they punish them. The parents’ plan must be implemented, and any resistance or negativism is not tolerated. Parents specify when the children have to eat, when they have to sleep, when they play, what they will put on, and who they should have as friends. High demands are set in terms of cleanliness, tidiness and it is expected for the child to have a high readiness to meet the parents’ demands. The parents consider that it is important for the child to be obedient and abide to

the parents’ plan. Such children generally start early with language, music, ballet and other classes.

These demands are generally set higher than children can bear, since there is constant pressure on them to be perfect in everything they undertake. If they fail, the children will feel frustrated because they cannot meet their parents’ expectations, and this may result in a feeling of inadequacy and guilt in later life. Such parental expectations create great pressure. In most cases, these expectations are unfulfilled.

Critical parents

Critical parents are those who criticise and are never satisfied with what the children do, and when they are satisfied, they are afraid to show it so as “not to spoil the child”. But, on the other hand, they are not afraid of criticising, warning and comparing their child with other children who are “smarter, more successful, better”. They do not even refrain from mocking and laughing at the child. Children thus lose self-confidence and security and begin to feel less worthy in comparison with others. They are consequently filled with dissatisfaction.

Excessive protectiveness: “Mummy will do it for you!”

The excessively protective attitude of some parents helps them to be good parents when children are very little and completely dependent. Later on, when children need to gradually become autonomous, such a manner becomes harmful. This applies, for instance, to a child who wants to eat by herself, put on her shoes by herself, reach something, and parents prevent her from doing so by saying, “You are little; you don’t know how to; careful, you’ll fall; you’ll make a mess; mummy will do it”. Faced with such over carefulness, children cannot become autonomous, they remain dependent on their parents, insecure, they lack confidence and become excessively shy.

Children sometimes react to such parental behaviour by throwing tantrums, having excessive demands, being disobedient at home, while outside the home they may be quiet and obedient, shy and insecure.

Overly protected children may have the feeling that the mother is always present, that she does not allow them to grow and take any risks, or that she will always see them as small children. Such children can often be demanding and selfish; they do not have friends, and even later on have difficulties in communicating with other people.

How do we become overly protective? The reasons vary, but there is always a special reason why a particular child has a special place in the parents’ life. This may have been triggered by an illness or some other condition of the child, sometimes this is a “long-awaited” child due to fertility problems, or a difficult, monitored pregnancy.

Sometimes there were serious marital problems preceding the child’s birth which might lead the mothers to experience the birth of a child as a reward for all the earlier difficulties and unfulfilled expectations. Overprotective mothers very often have an acute sense of responsibility, a close connection to the family and a prominent maternal instinct. The fathers in the family, in such cases, usually fall in the shadow, and do not have a sufficient sense of authority towards the mother and the child.

Some overprotected children behave in a rebellious, spiteful manner and can often act tyrannically towards their mothers who are extremely lenient and who appear helpless. Some typical situations can be witnessed in shops where small children demand that something be bought for them, and when they do not get their way, they start creating a performance to get what they want.

Excessive strictness: “You have to listen and behave!”

If the parents are strict, this usually means that they require excessive obedience, and regularly restrain their children in their small and normal pranks or aggressive play (screaming, jumping, running, banging), which children need, but which is very irritating for grown-ups. They often expect the kind of behaviour that is beyond the level of maturity of the children. For example, they expect a three-year-old boy to tidy up his toys himself, or they expect a child who is naturally frisky and playful to be calm when visiting someone, not to touch anything, not to throw things around, to be calm and well behaved in an instant. Such demands are excessive and inopportune.

Parents use loads of energy to mould their children in their own image, and they consider their strictness to be the best way to prepare their children for the future, because they do not want to spoil them. They take their child to a psychologist because she is disobedient or too lively. They try to achieve complete obedience through punishments or constant “nagging”. In so doing, the parents do not realise that their offspring do not understand most of these torturous “lectures”, which make them confused and afraid. Due to this excessive external control, these children do not develop their independence and self-initiative, and, with these elements, the ability to become involved in groups of peers as equals. They are usually very “refined and well-behaved”, and adults praise them to the sky, as opposed to their peers who reject them.

If punishment is applied, especially strict and physical punishment, children might be very calm and obedient at home, but in the company of their peers, in

kindergarten or school, they could be very aggressive, rough, and wanting to be “in charge” at all costs. All this shows that these children have not developed their internal behavioural control mechanisms.

Consequently, the result is similar to that in the case of excessively lenient parents. Since they lack sufficient control and understanding from their parents, these children do not develop their own control mechanism.

Children are afraid to openly confront strict parents, and thus try different, more or less concealed, ways of avoiding them. Such children may behave negligently, they do not hear what they are told, they forget, or, if they are forced to eat, they conceal the food. Sometimes, they have bodily reactions which give rise to psychosomatic conditions, such as headaches, stomach aches, pain around the heart, etc.

If your chid is, in one way or another, “less successful, slower in acquiring certain skills” than other children, it does not at all mean that she is less clever or lazier than others. This might mean that she is afraid or insecure.

According to psychologist J. Mascoll, some suggestions have to be followed to help your child achieve what both of you expect:

- Build a feeling of self-respect by showing your children that they are precious. If children have a good opinion of themselves, they will be better prepared to both acquire skills and deal with situations they will later be faced with.

- Prompt good and positive efforts, work or aptitudes, instead of criticising negative attempts and lack of aptitude. Do not overburden children with demands or duties. This might cause stress that will hinder success.

- Do not help your children too much, because they will never acquire self-confidence, but do not let them “agonise” over difficult tasks alone, either. Ideally, a balance should be struck between giving an initial push, where you can help children, and then letting them complete the task alone.

- Set expectations for your children, but do not set them too high. If the standards you set are higher than children can realistically achieve, they might gain the feeling that their performance will never be satisfactory. Gradually increase your demands.

- Use a ratio of 5 rewards to 1 punishment.

This is considered to be the most effective combination. The reward

may be praise, encouragement, or a warm smile, and punishment includes reproach, criticism, indifference, even a frown.

- First, it is important to comment on the positive sides of children’s efforts,

even if they are more difficult to find. Then, something interesting has to

be found in their work or behaviour, for instance an original idea, while the negative sides, which require constructive criticism, may be dealt with at the end. For several days, write down all the praise and

punishments that you have given the child. If it turns out that there were

fewer than 5 instances of praise to one punishment, it is high time you changed the way you are bringing up your child. If you continue to do the same, the child may have the impression that it can never fulfil expectations, and this depletes self-respect and produces anxiety.

- It is not advisable to excessively praise your children, either. They might

gain the impression that everything apart from what you praise is a failure. A child is in greater need to be seen and heard than to be praised. We can look at a drawing, and simply make a comment like: “This house is blue. You drew clouds, too”, or ask, “And what is this here?”

EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE

Mirjana Šprajc Bilen

“Anyone can become angry – that is easy. But to be angry with the right person to the right degree, at the right time, for the right purpose, and in the right way – that is not easy” (Aristotle)

“It is only with the heart that one can see rightly. What is essential is invisible to the eye (Antoine de Saint-Exupéry: The Little Prince)

Experience shows that the IQ (cognitive ability measured by IQ tests) of new generations of children has been increasing, while, on the other hand, their “emotional intelligence” has been decreasing. This means that children are becoming less capable of cooperating with others in resolving problems; of behaving in a friendly and kind manner; of respecting other people and empathising with them; of postponing gratification (reward); of being persistent, that is, self-motivating, so that they pull through in spite of difficulties; of understanding their own feelings and expressing them so that others also understand them, without being hurtful to themselves or others; of fostering a “positive attitude”; of being hopeful; and of having confidence in themselves and other people. These are all characteristics of an emotionally intelligent person.

Why is there a decline in the emotional competence and intelligence of the new generation?

For the simple reason that we do not sufficiently teach this to our children, and children are even less able to learn this spontaneously by imitating the adults they see, both in private and public life. Besides, we tend to imply that today kindness, understanding for other people, and integrity do not “pay off”, which sends a clear message to children about the type of behaviour we expect from them.

Since their earliest age, we have been teaching our children foreign languages, music, sports, computer skills and other skills that we think will improve their lives, make them happier and more successful. However, in the last few decades, there has been a growing awareness that rational knowledge and skills are not sufficient, and that emotional intelligence is, in fact, extremely important. Not only to make “better people”, but also to achieve what we call “success in life”. Some people hold that emotional intelligence is even more important than cognitive intelligence.

Emotional intelligence can be influenced more easily than cognitive intelligence, through learning and other educational processes, especially in childhood when the child is most capable of learning. It is in this period that some changes occur in the functioning of the brain, and the paths are sets for behaviours and experiences which later remain fixed. Little by little, children in this way create a collection of methods that they will use later in life to face various difficulties. The outcome of such learning is not only a successful child, but also a satisfied and healthy one.

In everyday life we do not encourage, but rather we prevent, the development of our children’s emotional intelligence. How?

- The child receives the ability to experience feelings/emotions at birth. If this ability is not stimulated in time, if the parents and the surroundings do not react to the child’s emotions at the earliest age, if they do not identify them, acknowledge them, if they do not respond to them, or name them, if they do not support the child in experiencing and appropriately expressing her feelings, there is the chance that the child will “give up” some emotions, learn to suppress and negate them. This is why a child needs so much attention and care in the first years of life.

- Children learn to hide their feelings to avoid a reaction from the surroundings.

However, “in good faith”, we do not always accept our children’s emotions or take them seriously… They upset us to the extent that we try to prevent them or behave as if they were not there… Grown-ups ask their children from the earliest age not to get angry, not to be sad, they persuade their children that it does not hurt, that they are not tired, thirsty, hungry, etc… Anger, hate, envy, jealousy or despair are not desirable, and sometimes neither are positive emotions, such as joy or being in love. Parents sometimes say things like “Stop it, you can dance and sing later”, “You can’t be afraid, there’s nothing to be afraid of”. As if fear needed a rationale! We say, “You love your baby brother, don’t you?” when the child is so jealous that she wishes the brother had never been born. When children hurt themselves or get an injection, we try to persuade them that this does not hurt, or we suggest, “It’s not that terrible, don’t exaggerate!” Try to imagine how you would feel if you were in pain and someone you loved and

trusted was trying to persuade you that you were making it up. Or if he wanted you to love your obnoxious boss because “he is so good and loves you”.

How do children understand these messages?

- In this way, we give children the message that their feelings are not important or desirable, that they are even unacceptable. Consequently, children feel that they themselves are unacceptable, too. They must not be as they are, they should be different in order for grown-ups to accept and love them.

- So, children build a poor image of themselves and develop an inferiority complex (“I am not good enough to be loved”). Such children are not aware of their virtues. The way they feel about themselves prevents them from believing that they also have good characteristics and abilities, and so they do not make use of them, they do not even make the effort, and consequently, they cannot experience success. Or, at the other extreme, in order to compensate for their feeling of inferiority, they make a lot of effort and achieve brilliant results, but, in spite of this, the feeling of depression and the bad self-image remain.

Children also care how we grown-ups feel

- Are we aware of ourselves and our emotions? If we do not recognise our feelings and do not know how to express them, or verbalise them, we cannot control them, or we control them sufficiently, which causes psychosomatic conditions and depression (“Those who cannot recognise their feelings, become their slaves”).

- Do we accept our feelings as they are, or do we suppress them?

- Can we relate our feelings to thoughts and behaviour?

- Are we aware how much we can affect our own mood?

Successful people consciously manage their emotions. They carefully observe their own moods, consciously channel them, and use them for their own benefit. Feelings are our source of energy, just as fuel is to a car. Feelings do not have us, we have feelings.

- There is always a choice, even with the most intense emotions. We can, for example, express strong anger either by crying and shouting, or by attacking or withdrawing.

How children perceive their parents (grown-ups)

Parents and other grown-ups sometimes forget that children have the capacity to perceive their parents’ (adults’) behaviour, even when parents try to hide their real feelings. Parents do this in good faith to protect their children from their bad mood. However, children recognise their parents’ mood, but due to their lack of maturity and their ignorance, they interpret it wrongly. At preschool age, children are generally egocentric: “All this is my fault. Mummy (or the kindergarten teacher, or daddy) is angry or sad because I am bad. This is why they cannot love me. It would have been better if I wasn’t here, if I hadn’t been born at all”.

Sometimes they might say something like this aloud, which causes consternation in the parents and other adults. Children may often maintain such an internal dialogue which can grow into a “life script”: “It would be best if I died”, and which accompanies them thought their lives.

This is why it is important to tell children when we are in a bad mood, when we are angry or sad, and explain to them that it is not their fault and that we love them. If it is, indeed, their fault, we should tell them so immediately, and accompany it with an appropriate consequence (punishment) to relieve the child from a feeling of guilt and to make her angry at us and not only at herself.

Many parents cannot stand the fact that their children are angry at them, that they are obstinate, angry or sad. This is the normal reaction of a parent or other caregiver. Some parents may even think in this situation that they are not good parents. However, the opposite is true. The fact that the parents do not let the children do whatever they like is a good indicator that the parents are actually trying to fulfil their role. If we required from children only what they themselves want, what use would we be? In order to be good educators, we sometimes need to be both demanding and “strict”, but also persistent and patient.

This does not apply to the situation where we are constantly in a bad mood and if we often “take it out” on the child. In such a case, there is no way to convince the child that we love her and that she is worthy of love and respect.

The educational style affects emotional intelligence

Authoritative education, where the roles of the parent and the child are clearly set, has proven to be better for the development of a child’s emotional intelligence. In such a relationship, it is clear which decisions are made by the parents, and which are the child’s responsibilities, and who listens to whom. For the development of emotional intelligence, it is better to be too strict but consistent, than too lenient and giving.

Emotional intelligence develops through the systematic teaching of children in all the areas mentioned above, such as the development of morality, encouragement towards cooperation and empathy, creation of trust, confidence, optimism, care for self and others, realistic thinking and resolving of problems, social skills, communication skills, sense of humour, acquiring friends, functioning in a group, good behaviour, success, the strength and control of emotions, non-verbal communication, the emotional strengthening of body and spirit, etc.

Conclusion

How can we stimulate the development of emotional intelligence and enable the child to be successful in the first years of life?

- By developing our own emotional intelligence

- By systematically teaching, not only through words, but also through experience.

The entire handbook suggests how to stimulate the psychomotor and emotional development of babies and small children in the first years of their lives and create the preconditions for a healthy life. The chapters on play, massage, educational procedures, and the stress of parenting all suggest simple ways of caring for your children, providing support and understanding, and participating in their emotional life. All these are methods to show our children, in a way that is acceptable to them, that we love them and that they are important to us. The way we treat them is the way they will later treat us, but also all the other people around them. When we develop their self-confidence and trust through play, socialising and understanding, we also stimulate psychomotor development, and we create what is necessary for children to exploit their capacities and to be successful. At the same time, we prevent later disruptions which are the plagues of today, such as depression (the most widespread illness of our time), aggressive behaviour, addictions, crime and illness.

Some suggestions on how to stimulate the development of preschool and school children’s emotional intelligence

- Be sincere with your children and require the same from them.